On February 25, 2022, the Government of Alberta confirmed that the Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Act (the “PPCLA”)[1]Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Act, c P-26.4 [Prompt Payment Act]. will come into force on August 29, 2022,[2]Builders’ Lien (Prompt Payment) Amendment Act, 2020, c 30; Proclaiming the Builders’ Lien (Prompt Payment) Amendment Act, 2020, OC 50/2022. and published the long-awaited Prompt Payment and Adjudication Regulation and the Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Forms Regulation (collectively the “Regulations”).[3]Prompt Payment and Adjudication Regulation, Alta Reg 23/2022 [Prompt Payment Regulations] and Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Forms Regulation, Alta Reg 22/2022. [Forms Regulations]. As discussed in our previous post, participants and stakeholders in Alberta’s construction industry have been in a state of limbo since 2020, awaiting the coming into force of the PPCLA and the major changes it contains. Most notably, several new provisions in the PPCLA left much of the interpretive heavy lifting to the Regulations. With the coming into force of the PPCLA now confirmed and the publication of the Regulations providing necessary detail, parties can now take steps to ensure they are fully prepared for these major changes.

As outlined in our initial post from November 2020, the PPCLA will change the construction industry in four main ways, by: (i) instituting prompt payment timeline requirements; (ii) allowing for progressive release of holdbacks; (iii) creating an adjudication system; and (iv) extending the default periods for filing a lien. While the PPCLA sets out the major changes, the Regulations provide the necessary detail to fill in the gaps and make these changes functional.

The highlights from the Regulations include:

- New transition rules: the PPCLA provided that only contracts entered into after the PPCLA was proclaimed would be subject to the significant updates brought about by Bill 37 and Bill 62 (most notably, the prompt payment and adjudication regimes). The Regulations now provide that contracts entered into before the PPCLA is in force, but that are scheduled to remain in effect for longer than 2 years after August 29, 2022, must be amended within 2 years to indicate that they are subject to the PPCLA.

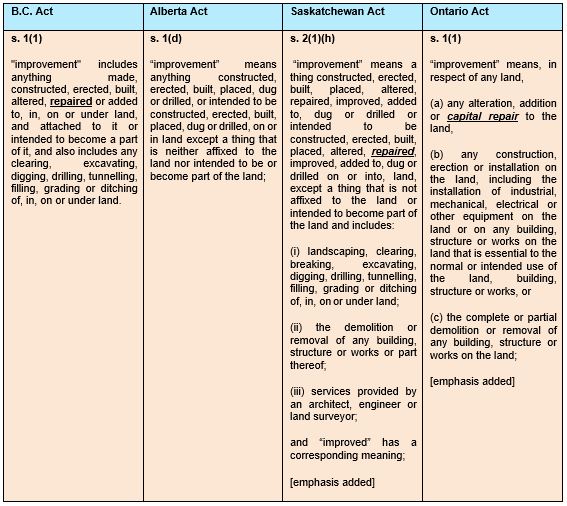

- Inclusion of engineers and architects: the Regulations stipulate that engineers and architects’ services are subject to the terms of the PPCLA where those services relate to an improvement.

- Adjudication process: details concerning the adjudication process have been given, the most salient of which is that a decision is to be made within 42 days of a notice of adjudication being filed and served (subject to an adjudicator extending the process by up to 10 days). Adjudicators will be appointed within 7 days of the adjudication notice, the claimant must submit its materials within 5 days of the adjudicator being appointed, and the respondent must submit its materials 12 days after it receives the claimants’ materials.

- Prescribed amount for progressive release of holdbacks: The PPCLA requires contracts which have a value over the prescribed amount to provide for a progressive release of the statutory holdback at least annually. The regulations set the prescribed amount at $10,000,000.

Prompt Payment Timeline

Pursuant to the PPCLA, the new prompt payment requirements are as follows:

- the prompt payment timelines are triggered by the issuance of a “proper invoice” which must be issued by all contractors and subcontractors at least every 31 days (subject to narrow exceptions).[4]Prompt Payment Act, s. 32.1(6). Within this 31-day limitation, the Regulations stipulate that the owner and contractor may agree to specific terms as to when a proper invoice may be delivered.[5]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 3.

- upon receipt of a proper invoice the owner must (i) dispute all or part of the proper invoice within 14 days, and (ii) pay all undisputed amounts in the proper invoice within 28 days.[6]Prompt Payment Act, ss. 32.2(1) and (2).

- a contractor must pay its subcontractors within 35 days of issuing a proper invoice to the owner[7]Prompt Payment Act. S. 32.3(4). or within 7 days of receiving: payment from the owner or a notice of non-payment from the owner,[8]Prompt Payment Act s. 32.3(1). unless the contractor issues its own notice of non-payment to its subcontractor, or serves the owner’s notice of non-payment, together with an undertaking that the Contractor will commence an adjudication no later than 21 days from issuing the notice;[9]Prompt Payment Act, ss. 32.2(5) and (6).

- the above payment deadlines and obligations apply down the construction pyramid, applying as between subcontractors and their sub-subcontractors.

The requirements for a “proper invoice” are set out in the PPCLA,[10]Prompt Payment Act, s. 32.1(1). whereas the Builders’ Lien Forms Amendment Regulation sets out the prescribed forms in which all notices described above must take.[11]Forms Regulations, Forms 1-14.

Adjudication Process

The PPCLA creates the statutory adjudication system, whereas the Regulations provide the details necessary to allow for the adjudication system to be put into place and become operational.

Unlike Ontario, the Regulations stipulate that Alberta may have multiple Nominating Authorities. Authorized Nominating Authorities will determine who will act as adjudicators by issuing a certificate of qualification to adjudicate to eligible individuals. Part 2 of the Regulations sets out eligibility requirements to become an adjudicator. The stipulated requirements include “10 years of relevant work experience in the construction sector” and “sufficient knowledge and experience” in areas including dispute resolution, contract law, adjudication process, ethics, and determination writing.[12]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 7(2). The Regulations also require ANAs to create a code of conduct which authorized adjudicators must adhere to.[13]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 10.

Further, the Regulations clarify the kinds of disputes that can be adjudicated and the rules surrounding same. With regards to the kinds of disputes that can be adjudicated, the Regulations list the following matters:

(a) the valuation of services or materials provided under the contract or subcontract;

(b) payment under the contract or subcontract;

(c) disputes that are the subject of a notice of non-payment under Part 3 of the Act;

(d) payment or non-payment of an amount retained as a major lien fund or minor lien fund and owed to a party during or at the end of a contract or subcontract, as the case may be; and

(e) any other matter in relation to the contract or subcontract, that the parties in dispute agree to, regardless of whether or not a proper invoice was issued or the claim is lienable.[14]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 19.

As for the rules surrounding the adjudication, the Regulations set out the following timelines and procedures:

| Steps | Days from service of notice of adjudication |

|---|---|

| Deadline for parties to agree on adjudicator | 4 |

| Deadline for Nominating Authority to appoint adjudicator | 11 |

| Deadline for claimant to provide its submission | 16 (or 5 days from appointment of adjudicator, whichever is earlier) |

| Deadline for respondent to provide its submission | 28 (or 12 days from receipt of claimant’s submission, whichever is earlier) |

| Deadline for adjudicator to issue order determining the dispute | 46 (or 30 days from receipt of claimant’s submission, whichever is earlier) |

Progressive Release of Holdbacks

The PPCLA makes progressive releases of holdback mandatory for projects where:

- the completion date is longer than one year, or the contract provides for payments of the holdback on a phased basis; and

- the contract price exceeds the prescribed amount,[15]Prompt Payment Act, s. 24.1. which pursuant to the Regulations is $10,000,000.[16]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 2(2).

As stipulated in the Regulations, where a contract does not specify a phased amount, the partial release of holdback payment must be made on an annual basis.[17]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 2(1).

Extension of default period for Liens

The PPCLA extends, or otherwise alters, the limitation periods for filing a lien as follows:

- for general construction, the limitation period is extended from 45 days to 60 days; and

- for any improvement primarily relating to “the furnishing of concrete as a material” or “work done in relation to concrete” the limitation period is extended to 90 days.[18]Prompt Payment Act, s. 27(2.21). However, the Regulations state that the 90 day limitation period does not apply to entities that install or use “ready-mix concrete”, as defined in the North … Continue reading

The Regulations clarify that the 90 day lien period does not apply to “entities that install or use ready-mix concrete”,[19]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 36. which is defined as the “mixing together water, cement, sand, gravel or crushed stone to make concrete, and delivering it to a purchaser in a plastic or unhardened state”[20]North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Canada 2017 Version 2.0, Code 32732 – Ready-Mix concrete manufacturing. This clarification suggests that the 90 day lien period would apply to concrete suppliers, or those engaged purely in preparatory activities (such as base preparation or installation of rebar), but not to the subcontractors who actually place and finish the concrete.

Transition Period

Any contract or subcontract entered into after August 29, 2022, will be governed by the new rules under the PPCLA and the Regulations.[21]Prompt Payment Act, s. 74(2). However, any contract entered into prior to August 29, 2022, will continue to be governed by the rules under the previous statute for a period of two-years.[22]Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 37. After the expiration of the two years, all construction contracts in Alberta will be subject to the PPCLA and the Regulations, and the new rules contained therein. While this calculus is relatively straightforward for most contracts, parties who have entered into contracts where work is scheduled to take just short of two years should consider the potential implications of any unforeseen delays on whether or not the new rules will apply.

As a result of this transition period, for the next two and a half years there will be contracts that are governed by the new rules and some governed by the old rules. Businesses and participants in Alberta’s construction industry will need to be cognisant of which rules apply to which contracts, as lien rights, payment rights and obligations, and dispute mechanisms will be significantly impacted. To this end, parties should consider reviewing and updating their contracts and internal processes to ensure contractual payment terms are consistent with the PPCLA and the Regulations.

Conclusion

The Regulations much needed clarity and refinement to the PPCLA, with the most substantial clarifications provided in regards to the adjudication process. The changes ushered in by the PPCLA and the Regulations are substantial. These changes will radically alter how the Alberta construction industry functions, particularly with regards to how and when parties are paid and how disputes are settled.

With proclamation of the PPCLA and the Regulations, it is incredibly important to have competent counsel with a deep understanding of construction law and the prompt payment and adjudication regime to ensure your business is prepared to thrive in this new legislative environment. The lawyers at McCarthy Tétrault have extensive experience in the construction industry and can help you navigate this complex legislative scheme.

References

| ↑1 | Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Act, c P-26.4 [Prompt Payment Act]. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Builders’ Lien (Prompt Payment) Amendment Act, 2020, c 30; Proclaiming the Builders’ Lien (Prompt Payment) Amendment Act, 2020, OC 50/2022. |

| ↑3 | Prompt Payment and Adjudication Regulation, Alta Reg 23/2022 [Prompt Payment Regulations] and Prompt Payment and Construction Lien Forms Regulation, Alta Reg 22/2022. [Forms Regulations]. |

| ↑4 | Prompt Payment Act, s. 32.1(6). |

| ↑5 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 3. |

| ↑6 | Prompt Payment Act, ss. 32.2(1) and (2). |

| ↑7 | Prompt Payment Act. S. 32.3(4). |

| ↑8 | Prompt Payment Act s. 32.3(1). |

| ↑9 | Prompt Payment Act, ss. 32.2(5) and (6). |

| ↑10 | Prompt Payment Act, s. 32.1(1). |

| ↑11 | Forms Regulations, Forms 1-14. |

| ↑12 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 7(2). |

| ↑13 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 10. |

| ↑14 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 19. |

| ↑15 | Prompt Payment Act, s. 24.1. |

| ↑16 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 2(2). |

| ↑17 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 2(1). |

| ↑18 | Prompt Payment Act, s. 27(2.21). However, the Regulations state that the 90 day limitation period does not apply to entities that install or use “ready-mix concrete”, as defined in the North American Industry Classification System. |

| ↑19 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 36. |

| ↑20 | North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Canada 2017 Version 2.0, Code 32732 – Ready-Mix concrete manufacturing. |

| ↑21 | Prompt Payment Act, s. 74(2). |

| ↑22 | Prompt Payment Regulations, s. 37. |