Introduction

I often explain the difference between non-lienable maintenance and repair work on the one hand, and lienable construction work on the other, using the analogy of a landscaper called to a worksite. In one scenario he’s asked to mow the grass and trim the hedges. In another, he’s asked to terraform the entire property, complete with a new deck, sheds, a koi pond, and a stone pathway. The first scenario is non-lienable maintenance, while the second is lienable construction.

Not every worksite, however, involves a koi pond. When dealing with (for example) heavy industrial projects or the energy sector, repair and maintenance work might involve the comprehensive replacement of very large and very expensive machinery and equipment, or massive investment in capital repairs. The difference between maintenance, repair, and construction is often less clear, and courts frequently struggle with where to draw the line. To assist you, dear reader, in making this determination, we have reviewed and summarized the current state of the law in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario.

Executive Summary

The lines of authority respecting the division between maintenance work, repair work, and construction work in Canada have generally divided into two camps: (i) emphasis on the characterization, effect or intended effect of the work in Ontario case law, or (ii) emphasis on the characterization, effect or intended effect of the overall project in B.C., Alberta, and Saskatchewan.

In Ontario, the emphasis is on the nature of the work: maintenance or repair work intended to improve the value of the land is likely lienable (as such work is considered an “improvement” under the statute), whereas work that is intended merely to maintain the status quo is likely not lienable.

In B.C., Alberta, and Saskatchewan, the emphasis is on whether the work or service is necessary or supportive for the completion of the overall project, wherein the overall project is the improvement (and the overall project includes the physical construction of a thing). To put this in perspective, if the overall project is the construction of a shopping centre, then all work and services associated with that construction are lienable, including maintenance, cleaning, inspection, security, temporary water services, the delivery of porta-potties to the site, heating and hoarding, etc.

Legislative Comparison

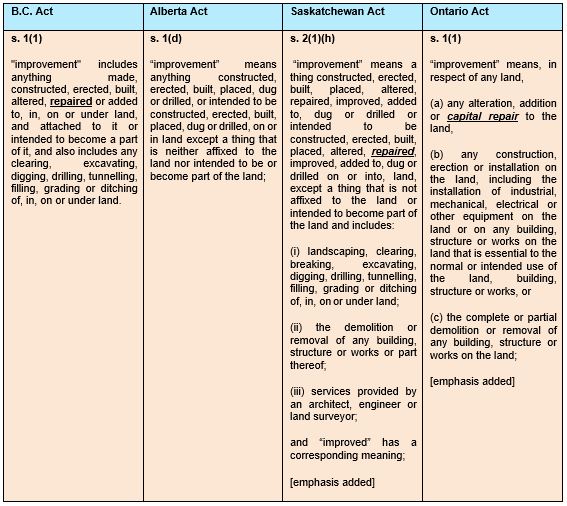

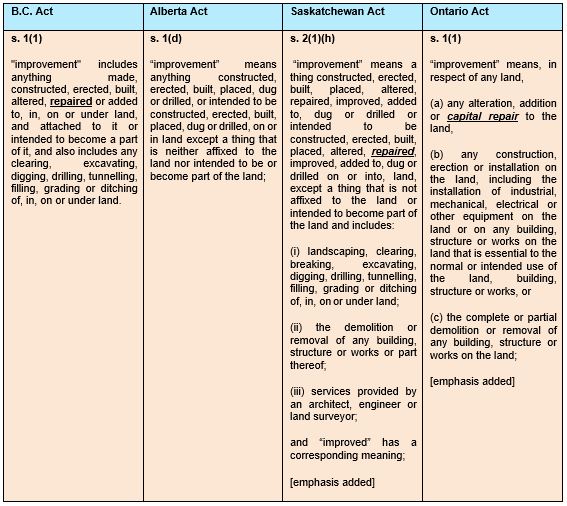

In each of these jurisdictions, analysis begins with the definition of an “improvement”, because for work or services to be lienable, that work or service must be provided to an improvement. In B.C, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, an improvement includes “repair” or “capital repair” to land in question; Alberta hasn’t included the same terms within its definition of same.

(a) British Columbia

While there’s limited case law in B.C. on the lienability of maintenance work, it’s clear – given the inclusion of “repair” work in the B.C. Builders Lien Act’s definition of improvement – that repair projects (likely capital repair projects) can constitute an “improvement” and therefore sustain lien rights. Given the currently available case law in B.C., it also appears that B.C.’s courts are mostly in harmony with the developing lines of authority in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

In the 2011 case of Alexander Construction Ltd. v Al-ZaibakEyeglasses, the British Columbia Supreme Court needed to decide whether the lien claimant’s provision of basic inspection and maintenance work could be considered “work” within the meaning of section 1(5) of the B.C. Act, and therefore sustain lien rights that would have otherwise expired. The Court determined that while this work was “minimal”, given a liberal reading, it was still sufficient to constitute work on the larger improvement (the construction of a home). The Court noted that while the subject efforts “did not move the project any closer to conclusion, they prevented deterioration to the project that would further delay its completion.” In other words, the Court placed emphasis not on the nature or characterization of the work itself, but rather on the work’s connection to the larger overall improvement project.

In a similar line, in Shelly Morris Business Services Ltd. v Syncor Solutions Limited the Supreme Court of British Columbia:

- noted that the definition of “improvement” is inclusive and can bear meanings other than those included in section 1 of the B.C. Act, as long as they do not subtract from the prescribed definition;

- emphasized that “improvement” means an improvement to the property itself; and

- held that the lien claimant must have contributed physically to the improvement of the site in question.

Both Alexander Construction and Shelly Morris are consistent with case law and statutory interpretation in Alberta and Saskatchewan, so the guidance from the jurisprudence in those provinces may be instructive for similar B.C. determinations.

(b) Alberta

Alberta generally draws a much clearer line between physical construction of an improvement (which is lienable) and maintenance work (which is not) than jurisdictions such as Ontario. Given the absence of the terms “repair” and “capital repair” in the Alberta Act, Alberta courts have put more emphasis on the nature or characterization of the overall project rather than the effect or intended effect of the work in question.

Identification of the “improvement” in Alberta is determined by reference to the “overall project” and not the specific work being undertaken, so if nothing new is actually being physically constructed, there is likely not an improvement and thus likely no lien rights. On the other hand, if the overall project meets the definition of an improvement, then nearly any type of work or service provided to that larger project – and that is a necessary or supporting part of physical construction – will likely be lienable.

Fortunately, the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench provided clear guidance on the specific circumstances in which maintenance will and will not be lienable in the 2021 case of Young EnergyServe Inc v LR Ltd, where it dealt with the question of repair and maintenance work during a turnaround project at a gas processing plant.

In finding that a filed lien was not valid, the Court held that “the cleaning, repairing, and relining the interior of tanks and pressure vessels and replacing old or faulty piping and pressure valves are not directly related to the process of construction” and that “[t]hose activities are more appropriately characterized as being in the nature of maintenance.”

First, the Court acknowledged that the recent approach taken in Alberta is to consider an “improvement” from the perspective of the “overall project”:

There is no evidence to suggest that the Turnaround Project was a component of a larger construction project on the Mazeppa Lands. In particular, there is no evidence: (i) that the overall project in this case was any broader than the Turnaround Project; or (ii) that the Turnaround Project was a component of the construction of the Mazeppa Power Plant.

I mention this point for context because the Alberta Courts considers “improvement” from the perspective of the “overall project” involved: Re Davidson Well Drilling Limited, 2016 ABQB 416 at para 79 [Davidson Well Drilling]. Based on the facts underlying this case, the Work under the Turnaround Project was not part of an overall project to build a structure on the Mazeppa Lands: see Trotter and Morton Building Technologies Inc v Stealth Acoustical & Emission Control Inc, 2017 ABQB 262 (Master Prowse) at paras 54, 55, and 58. […]

The Court noted that both the Supreme Court of Canada and the Alberta Court of Appeal have held that, in order to establish lien rights, a claimant must first strictly comply with the relevant statutory pre-requisites to the creation of the right. However, courts are then entitled to liberally interpret other matters dealt with in that statute. In this case, there was no evidence that the project in question was a component of the overall project to build a new structure on the lands.

Second, the Court reiterated and summarized the Alberta case law, which draws a clear distinction between work involved in the construction of an improvement versus subsequent maintenance, stating:

Alberta courts have determined that services must be directly related to the creation or construction of an improvement to entitle the provider to a lien under the Alberta BLA. As a result, the Courts in this province have, as a rule, rejected claims related to the maintenance and the remediation of lands.

The Alberta Court of Appeal has reinforced this interpretative approach by commenting that when assessing whether an applicant and the work it performs fall within the terms of the Alberta BLA, the proper approach is to give a strict interpretation to the relevant provisions: see Calgary Landscape at paras 13-19. That appellate Court was cited, and it stated that “[a]lthough it is clear that services need not be physically performed upon the improvement to fall with the meaning of the [Alberta BLA] they must […] be directly related to the process of construction”: Hett v Samoth Realty Projects Limited, 1977 ALTASCAD 120 (CanLII), 3 Alta LR (2d) 97 at para 25 (CA); see also Leduc Estates Ltd v IBI Group, 1992 CanLII 6104 (AB QB) at para 34.

In adopting this interpretation, the Alberta Court of Appeal confirmed that while services need not be physically performed for the improvement to fall within the meaning of the [Alberta Act], they must be directly related to the process of construction. As a result, the Alberta Courts have drawn a clear distinction between the work involved in the construction of an improvement as part of the construction process on a building site and the subsequent maintenance. As held in Calgary Landscape the former is “obviously related to ‘making or constructing’ while the latter, falling in the category of maintenance, clearly is not”: at para 12. [emphasis added]

Finally, the Court addressed jurisprudence under the Ontario and Saskatchewan Acts. With respect to the Ontario version, the Court noted that it would be inappropriate to rely on its definition of “improvement” because of a clear difference in the language between the Alberta and Ontario Acts; specifically, the use of the phrase “alternation, addition or repair” in the definition of “improvement” under the Ontario Act, which is absent in the Alberta Act. With respect to the Saskatchewan version, the Court referred to Re Davidson Well Drilling Limited, wherein Madam Justice J.M. Ross had previously acknowledged that the definition of “improvement” under the Saskatchewan Act is virtually identical to the Alberta Act. The Court ultimately used these factors to further distinguish the definition of “improvement” under the Ontario and Alberta Acts.

(c) Ontario

In summary of what follows below, a party in Ontario may be entitled to lien rights where the work is intended to improve the value of the land (as in the case of “capital repair” work), but not in situations where the work is intended to maintain the status quo (i.e. non-lienable maintenance work). As such, the emphasis in Ontario case law appears to be on the effect or even the ‘intended effect’ of the work, rather than characterization of the larger “overall project” as there is, for example, in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

In 310 Waste Ltd. v Casboro Industries Ltd., the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (Divisional Court) dealt with an appeal by a landowner from a judgement dismissing an application to discharge a lien associated with 310 Waste Ltd.’s removal of hundreds of thousands of tires from a dumpsite owned by Casboro Industries Ltd. Casboro, as landowner, retained 310, as contractor, when it was ordered by the Ministry of Environment to remove the tires from their dumpsite. When Casboro failed to pay amounts owing for the removal of the tires, 310 registered a lien against the associated lands.

On appeal, the Court agreed with the application judge’s rationale that maintenance (such as the removal of snow) did not give rise to a construction lien. However, the Court also agreed with the application judge’s conclusion that the removal of the tires, which were declared “waste” and a “contaminant” within the meaning of the Environmental Protection Act, “clearly enhanced the value of the land” and was therefore considered an “improvement” of the land as defined by the old Ontario Act, and held the lien filed by 310 to be valid. The rationale used in this decision is somewhat suspect given that merely “enhanc[ing] the value of land” without more (i.e. physical construction) has been rejected in many other contexts as an adequate justification to establish lien rights. Albeit, removing “contamination” through the use of physical labour likely does meet the established definition of construction.

Later, in U.S. Steel Canada Inc., Re, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice found that the following supply of goods and services could give rise to lien rights: (i) the adding of soil and the supply of flower plants; and (ii) spraying for weeds where the contractor provided its own material; and removing weeds, spreading dirt and gravel, and installing cloth. Further, the Court went so far as to suggest that “grounds keeping” would give rise to a lien right, although this conflicts with more strict interpretations from other jurisdictions.

U.S. Steel created some uncertainty for owners and contractors alike, as landscape maintenance contractors in Ontario now had a valid claim that their services could be lienable. As a means to provide clarity, the Ontario legislature passed the Construction Lien Act Amendment Act, on December 12, 2017. Subsequently, on July 1, 2018, changes to the definition of “improvement” came into effect under the new, renamed Ontario Act, which succeeded the old Ontario Act.

Where the old Ontario Act defined improvement to include “any alteration, addition or repair to the land”, the new Ontario Act specifies “capital repair” instead of “repair” to the land. These amendments were based on recommendations from an extensive report prepared by the Ontario government in 2016 which addressed the distinction between repairs and maintenance by making reference to the Income Tax Act. Specifically, the report indicated that while capital repairs are intended to improve the land, “maintenance” is intended to maintain the original condition of the land and is not intended to form part of an “improvement”, and therefore does not result in a lien right. This distinction puts the emphasis in Ontario on the effect or intent of the work (i.e. improvement, addition, “value-add” etc.), whereas Alberta and Saskatchewan courts are more interested in the nature of the labour, and whether it’s best characterized as actual physical construction or mere maintenance.

(d) Saskatchewan

The question of lienability of maintenance work has not been dealt with as directly in Saskatchewan as it has in Alberta and Ontario. As always, whether maintenance work is lienable will depend on whether such work contributes to the “improvement” of the lands in question.

In Crescent Point Energy Corp. v DFA Transport Ltd., the Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench considered, among other things, whether service hauling of various fluids to or from well sites constituted an “improvement” under the Saskatchewan Act and could therefore result in valid lien rights. Crescent Point was an Alberta partnership carrying on business in Saskatchewan in the exploration, production, sales and marketing of petroleum, natural gas and related hydrocarbons. DFA Transport was a Saskatchewan transport company that supplied Crescent Point with various fluid hauling services.

When Crescent Point ceased payments, claiming overbilling, DFA Transport filed an action and application to compel Crescent Point to pay all outstanding amounts and notified Crescent Point of a Claim of Lien registered against their interests in Saskatchewan.

The parties agreed that DFA Transport’s work included:

- Production hauling: transporting water or oil from well sites to processing facilities or disposal sites;

- Service hauling: transporting water, kill fluid, and other liquids to or from well sites or battery sites in connection with maintenance and repairs to wells or batteries performed by third parties; and

- Completion hauling: transporting water to well sites to fill frac storage tanks and transporting flowback liquid away from well sites.

In determining the validity of any lien rights as a result of DFA Transport’s work for Crescent Point, the Court considered whether the work constituted an “improvement” within the meaning of the Saskatchewan Act. Specifically, the Court relied on its previous decision in Points North Freight Forwarding Inc. v Coates Drilling Ltd. (Trustee of), which held that if a person provides a service which has a direct and real contribution to the construction of an improvement, that person will be entitled to make a lien claim.

The Court also referred to Boomer Transport Ltd. v Prevail Energy Canada Ltd., where it had previously held that services that included, inter alia, the pumping out and hauling of water on a continuous basis, where that water was required to be extracted from an oil-water mixture being pumped from the ground through an oil well head, were an integral part of the production of oil for market and thus met the definition of a lienable claim.

Given the foregoing, the Court ultimately held that DFA Transport’s Claim of Lien was valid because, by servicing Crescent Point’s well sites and transporting fluids to and from the well sites, such services were an “improvement” under the Saskatchewan Act.

Post Script

Posts on this website take many forms, from brief blog posts to deep-dive features which eventually form the foundation for updates to one or more of my books. This post is, obviously, of the latter variety. If you want (even more) up-to-date analysis on this topic and others, I suggest subscribing to (or purchasing a physical copy of) Heintzman, West and Goldsmith on Canadian Building Contracts, 5th Edition.